Joan Ross

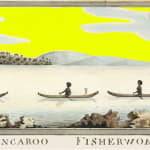

Barangaroo Fisherwoman, 2021

hand-painted digital collage

69 x 200 cm

edition of 6 + 2 AP

Source material: ‘Ban nel long [Bennelong] meeting the Governor by appointment after he was wounded by Willemaring in September 1790’ by The Port Jackson Painter, watercolour, this work shows Governor...

Source material:

‘Ban nel long [Bennelong] meeting the Governor by appointment after he was wounded by Willemaring in September 1790’ by The Port Jackson Painter, watercolour, this work shows Governor Arthur Phillip being rowed out to meet Bennelong to attempt a reconciliation after the governor had been gravely wounded by a spear at Manly. Barangaroo is pictured in the second canoe from the left. Watling Collection, Natural History Museum, UK.

Aboriginal woman in a canoe… attributed to Joseph Tetley, watercolour, circa 1805, State Library of NSW

Barangaroo was one of the more powerful figures in Sydney’s early history. She was a Cameragaleon woman, from the country around North Harbour and Manly.

Barangaroo was found on first meeting to be statuesque to the point of striking and more than a little frightening. She had presence and authority. On first contact, officers in the day estimated her age at about 40, and this is significant. She was older, more mature, and possessed wisdom, status and influence far beyond the much younger women the officers knew.

Barangaroo was a fisherwoman. Eora women like her were the main food providers for their families, and the staple food source of the coastal people around Sydney was fish. Unlike men, who stood motionless in the shore and speared fish with multi-pronged spears, or fish-gigs ( callarr and mooting), the women fished from their bark canoes (nowie) with lines and hooks.

Eora women’s skills in fishing, swimming, diving and canoeing were extraordinary. The women skimmed the waters in their simple bark canoes with fires lit on clay pads for warmth and cooking. The officers were fascinated; they wondered how on earth the women could manage these ‘contemptible skiffs’, fishing tackle, onboard fire, small children and babies at the breast, in surf that would terrify their toughest sailors.

Barangaroo had a baby girl in 1791. She gave birth alone, somewhere in the bush on the edge of the town. Lieutenant Governor David Collins came quietly to see her afterwards and was astonished to see her ‘walking about alone, picking up sticks to mend her fire’, the tiny reddish infant lying on soft bark on the ground. But she did not live long after the birth. She was cremated, with her fishing gear beside her, in a small ceremony. Bennelong her partner, buried Barrangaroo’s ashes carefully in the garden of Government House.

References

Val Attenbrow, Sydney’s Aboriginal Past: Investigation the Archaeological and Historical Records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010

Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2010

Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003

‘Ban nel long [Bennelong] meeting the Governor by appointment after he was wounded by Willemaring in September 1790’ by The Port Jackson Painter, watercolour, this work shows Governor Arthur Phillip being rowed out to meet Bennelong to attempt a reconciliation after the governor had been gravely wounded by a spear at Manly. Barangaroo is pictured in the second canoe from the left. Watling Collection, Natural History Museum, UK.

Aboriginal woman in a canoe… attributed to Joseph Tetley, watercolour, circa 1805, State Library of NSW

Barangaroo was one of the more powerful figures in Sydney’s early history. She was a Cameragaleon woman, from the country around North Harbour and Manly.

Barangaroo was found on first meeting to be statuesque to the point of striking and more than a little frightening. She had presence and authority. On first contact, officers in the day estimated her age at about 40, and this is significant. She was older, more mature, and possessed wisdom, status and influence far beyond the much younger women the officers knew.

Barangaroo was a fisherwoman. Eora women like her were the main food providers for their families, and the staple food source of the coastal people around Sydney was fish. Unlike men, who stood motionless in the shore and speared fish with multi-pronged spears, or fish-gigs ( callarr and mooting), the women fished from their bark canoes (nowie) with lines and hooks.

Eora women’s skills in fishing, swimming, diving and canoeing were extraordinary. The women skimmed the waters in their simple bark canoes with fires lit on clay pads for warmth and cooking. The officers were fascinated; they wondered how on earth the women could manage these ‘contemptible skiffs’, fishing tackle, onboard fire, small children and babies at the breast, in surf that would terrify their toughest sailors.

Barangaroo had a baby girl in 1791. She gave birth alone, somewhere in the bush on the edge of the town. Lieutenant Governor David Collins came quietly to see her afterwards and was astonished to see her ‘walking about alone, picking up sticks to mend her fire’, the tiny reddish infant lying on soft bark on the ground. But she did not live long after the birth. She was cremated, with her fishing gear beside her, in a small ceremony. Bennelong her partner, buried Barrangaroo’s ashes carefully in the garden of Government House.

References

Val Attenbrow, Sydney’s Aboriginal Past: Investigation the Archaeological and Historical Records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010

Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2010

Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003