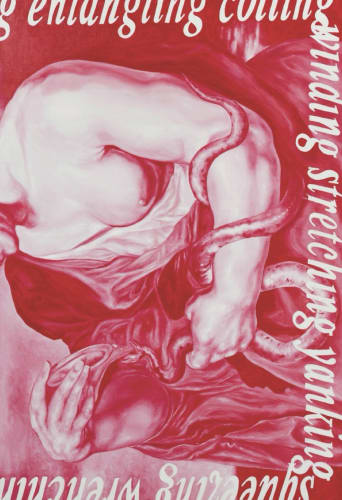

Faced with pain without answer, fantasy wins in a bid for control of your own situation. Practitioners’ tools and methods have not served your body, now you succeed the role. In your surgical suite, your captive audience is waiting for elucidation on the secrets you have

discovered amidst the knots and growths. You are the primary surgeon and primary subject. Maybe here the desire for autonomy over a bodily betrayal can be won, no longer stifled by diagnostic confusion and timelines, or choosing the lesser of two progesterone pain, metal, snipping and ending evils: fantasies formed in sick rest beds wherein you may run amuck excising the gnarling growths and groans in completion. Mattress as body, mattress as bed, patient as surgeon and surgical fantasies in my head.

As if you could put a rope around pain and tie it down. Pain, the vile intruder that can masquerade as madness in extremity. The religious overlay on the social and medical response: ‘Pain, the originator of madness, stood as the opposite of reason and human choice.’ (Esther Cohen, ‘The Modulated Scream: Pain in Late Medieval Culture’.) Blood mysticism, the problematising of pain being embodied, because should not the perfection of sacred pain require a locus somewhere outside the imperfect physical vessel? The infernal contradiction whereby a woman screaming out her pain in religious context might be venerated or even sanctified, but quotidian personal pain from every female non-saint

should remain private, silent.

“It is a view of suffering, of the pain of others, that is rooted in religious thinking, which links pain to sacrifice, sacrifice to exaltation - a view that could not be more alien to a modern sensibility, which regards suffering as something that is a mistake or an accident or a crime. Something to be fixed. Something to be refused.” (Susan Sontag, ‘Regarding the Pain of

Others’)

Endometriosis pain is pain that only comes from endometriosis, a shared lagoon of bottomless depth in which only the experienced may be immersed, inaccessible to those who are not – but no-one else ever asks for directions or complains of exclusion.

And yet all pain is also one pain, finally; those who live in pain within their own categories have communion at the universal pain banquet.

We can understand. We can respect. We cannot share. Each portion of our pain is our own, as indivisible as it is invisible.

“(T)here is an inevitable distance between object and subject, between witness and victim, distance that is not only in the kind and in the level of suffering we (we as observers, and others as victims) experience, but simply in space and time.” (T.S. Tsonchev, ‘Witnessing

the Pain of Others’)

Living in pain can also mean living in fantasy. Most literally, and banally, the fantasy world that. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy exponents advocate as an antidote. ‘Foetal on the floor, clutching your stomach and whimpering? Imagine instead you are in a hammock

on a balmy beach and feel the soft breeze kissing your skin!’ Fantasy more pervasively and importantly as a response to pain’s overpowering omnipresence. Fantasy as an act of wild optimism when it is illogical to construct any vision of a life where pain does not dictate your days. The fantasy also of gaining or reclaiming autonomy over your own body in the face

of inadequate responses from a medical authority. Dreaming yourself back to selfhood with the same instrument – your mind – that registers all that incapacitating pain.

Pain perverts time – stopping it, stretching it, contorting it into abnormal shapes. Pain thrashes the strongest adversary. Pain is as extant as a rainbow or birdsong or the taste of blueberries, but it defeats description. It makes language impotent. We express pain in sounds and disjointed syllables, unable to find adequacy in coherence. We use language

that is superlative but not fully direct, unable to approach the task of describing pain head-on, reaching repeatedly for phrases equally well or badly suited to describing another ineffability, love: smitten; hopeless; headless; mad; bursting; brought to one’s knees; out of one’s head; dizzy; dazed; delirious. We call pain ‘exquisite’.

It poses insurmountable artistic challenges, but the quest to depict it, to reify it and communicate it is necessary and endless. We have to tell our pain. It is a compulsion. Also, arguably, a moral duty. Sontag again: “Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers.” To say: I will out something that is wholly within. I will scream the unsayable. I will invite you to stand and look at this smashed and reassembled mirror. I will undouble and rise above the noise of pain and show you truths refracted in every facet fragment fracture, and maybe whisper my fantasies too.