No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality.

Haunting of Hill House (1959) by Shirley Jackson

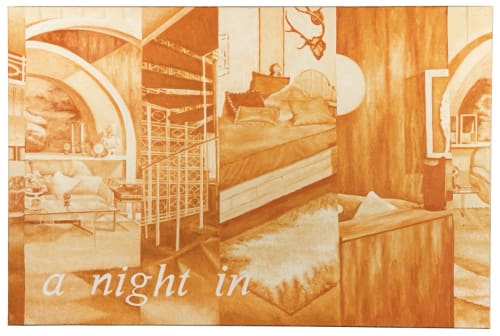

When I first arrived in the house, we got along amicably. I would polish the floors and wipe down the walls, change bulbs when they broke and consult specialists when the needs of the house exceeded the realms of my knowledge. I was not necessarily the best tenant: wine stains littered floors and old nails jammed into the walls hung pictures of boots and clowns. But I did my best to keep the house in order. In exchange for my services, the house provided safe shelter. The house kept out the weather and the creeps and kept me comfortable. I lounged and luxuriated in each of its discrete rooms. It is true: I always knew that as I grew, the house too would grow, degenerate. I did not, however, ever expect the house to become angry, and I did not expect the house to try expelling me from its walls.

One day, suddenly, it seemed the house did not want me anymore. The architecture corrupted. The house went gone wrong in ways that feel impossible. I understand Danielewski when I see the walls have become longer than the frame of the house. I understand The House of the Living when I realise the house is not a place I can leave. It grows leprous and wails when made aware of its own work. It cannot be left, or silenced, or reasoned with.

Now, the house opens its windows at night in the hopes that any number of characters may come in and enact their violence upon me. Stand-up comedians may try their experimental sets in my living room and psychopaths may cut the pockets from all of my coats. Some days it may be cruel and put table edges where my hips will inevitably meet them at velocity, hoping the inflicted injury will be reason enough for me to pack bags and vamoose.

I do not think the house realises that I cannot leave. Some days are kinder, and the pool will

nervously insist that it is of no use to me — for today at least. As I look to the chandelier for light or the fireplace for warmth, I find they wobble and glitch. They are not to be trusted. I suspect the flames have loftier, more vitriolic aims than the simple provision of light. Growths seep rotten from the wooden walls and oobleck-like substances leak from the bath. Interestingly and suspiciously enough the house is still pretty. It is preened and polished because every measure is still taken to maintain it. I held up my end of the bargain.

Still, all of this is to be expected. There are very few measures to be taken. I ask: what happens when your safe space is not as safe as you think? How do you reconcile the habitation of such a place?

You must strive to understand this house, as this house is yours. This shelter is not necessarily

confined to mud, concrete, steel, asbestos and wood. It is bones, tendons, arteries and blood. Alive, with its architecture eerily familiar, each room is an appendage, some with strange and seemingly irreconcilable corruptions. Professionals will tell you it is simply the house settling, or that you should consult a priest to have the house exorcised. You ring the priest, and he says he simply can’t imagine how a house so young would be so angry. As such it must not be haunted. So you are left, you and the house. Skin as wallpaper, bones as load bearing beams. You must sit with the house in all its frustrated machinations and hope for a change of heart.

The house is angry. The house allows such things to carry on.