With myriad references to museum curios, colonial landowners, and lashings of highlighter yellow, the aesthetic of Sydney-based artist Joan Ross is instantly recognisable.

Since the late 1980s Ross has worked across video, sculpture, painting, installation and drawing. Responding to the work of colonial-era British painters like Thomas Gainsborough and Joseph Lycett, she is deeply critical of the heavy-handed colonial (and contemporary) approach to ownership and collecting. How these invasive practices have impacted Indigenous history is a primary concern of her work, and was explored in Collector’s Paradise, a digital projection recently displayed across the façade of the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Canberra.

Here, Ross shares the stories behind five recent works.

JOAN ROSS: This video starts with moths being attracted to a flame. For me, moths going to the light are like humans and greed. I’ve used objects from the National Gallery of Australia collection to question how we collect. I’m very excited to have a work projected onto a museum that is essentially about criticising museum collections. There are many underlying themes in this work—consumerism, climate, colonisation. Colonisation is a central idea, but I also see colonisation as encompassing those other things as well. The moths start a series of tremors leading to rain, a flood, and eventually the building smashes down and shuts all the lights off, making way for nature to renew the landscape. Overall, I’m collapsing the colonial mindset. It’s a fun work to watch: it’s heavy with metaphor, it’s really meaningful and there were some beautiful moments in watching the audience.

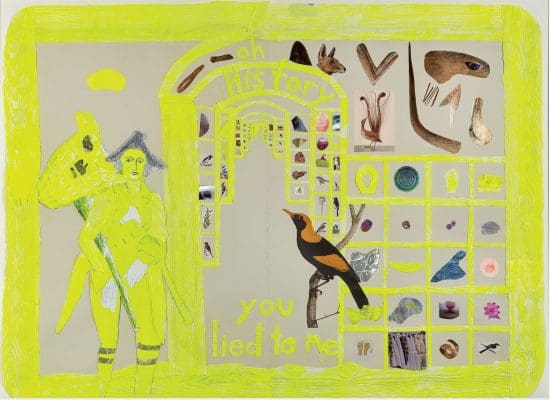

JOAN ROSS: I often imbue a sense of emotionality in my work. It is almost what fuels it and allows me to get more pleasure out of it. This work is based on colonial history and museum collections, but it is also relating to a personal experience of someone actually lying to me. There are visual references to Sarah Stone’s late 18th century watercolours of objects in London’s Leverian Museum, a place where the halls and rooms go back and back like infinity. With the high-vis yellow, I started using it soon after 9/11 and insurance premiums were going up. People were being made to sign documents to commit to wearing fluoro colours for safety. It seemed to catch on like wildfire and everybody started wearing it—not just roadworkers and police but plumbers and tradies as well. It’s at a point where there is so much fluoro we no longer see it. People know the intrinsic power of that colour, so it not only holds fear, it holds power. When you are wearing it, you can do anything you want to the land without being questioned.

JOAN ROSS: Two friends of mine modelled for these figures. I went to the National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) costume department and borrowed shoes and outfits. I bought wigs and masks online. Really bland masks. We only had 10 minutes to dress up before we went to the University of Technology in Sydney where artist Louis Pratt 3D scanned everything and printed it out as a 3D sculpture.

The night before, I made the mountain the figures are holding which I constructed from foam. The original is in my 2018 video I give you a mountain, and has graffiti all over it. The graffiti relates to Indigenous sites in the Wollemi National Park where someone had graffitied over ancient markings.

In a broader sense, it’s about tagging and claiming ownership—people graffitiing on something that isn’t their territory. It is a colonial man giving another colonial man a mountain. I don’t think you can give away land that belongs to someone else. This is very clearly an Indigenous country and Indigenous people’s land. There’s no question.

JOAN ROSS: When I make a work, I’m aware people want their place in it. My initial experience with virtual reality (VR) was that it was a self-centred space and not an easy place for making art. A few months later, [collaborator] Josh Harle and I were being interviewed by [artist] Giselle Stanborough and she asked a question about the relationship between VR and colonisation. After the interview my head exploded with ideas. Josh and I immediately applied for an Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) grant and got it done in a couple of hours.

In Did you ask the river? you enter the VR as a colonial woman. Whatever you do causes destruction – when you reach for things you accidentally start knocking trees over. Cows come into view and start mooing; you throw hand grenades and factories appear and start to take over the landscape. If you pat the rabbits, they start multiplying. The more you touch them, the more they multiply. You wreck the world even though you didn’t mean to. When we get pleasure from things or feel we have power, we rarely want to stop what we are doing. We are complicit.

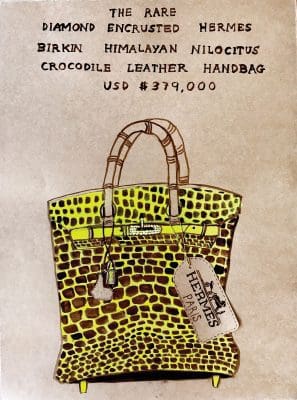

JOAN ROSS: For me, this work is about my distaste for people placing their value in what they see as rare. I began by looking up the most expensive handbags in the world. It’s like these objects can project the owner into a higher echelon. I find that disturbing. There is no true value in this designer world, it’s a very fake reality.

Many of my works contain references to designer objects. In one of my videos I use a Louis Vuitton designer garbage bag, which I think epitomises this. I have a natural disinclination about our obsession with interior design, the social pressures around that kind of stuff—it’s not helpful to our soul. I also don’t like that Hermès is building a crocodile farm in the Northern Territory. I’ve had a big love for animals and insects my whole life. I’ve written poems about mosquitos. When I see trays of dead insects, butterflies, moths and birds, I don’t feel comfortable about it.