-

Dylan and Kyra in their Meanjin studio.

Dylan and Kyra in their Meanjin studio. -

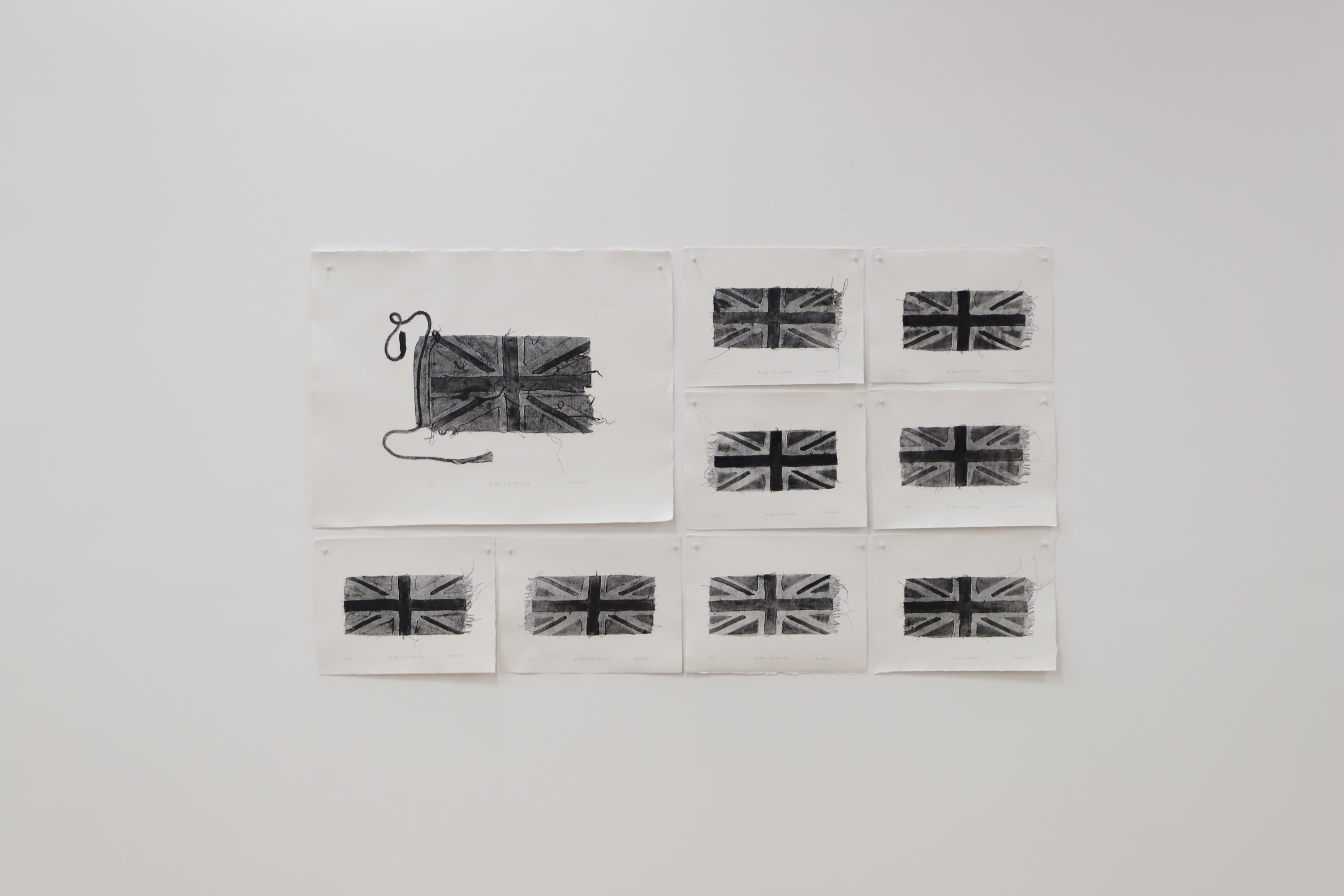

No Blak in the Union Jack.

Kyra Mancktelow’s series No Blak in the Union Jack takes its title from British Academic Paul Gilroy’s book ‘There Ain't No Black in the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation’.

Written in 1987, Gilroy’s book is a powerful indictment of then current attitudes to race in Great Britain. The author accused British intellectuals and politicians on both sides of the political divide of refusing to take race seriously.

Flags have different interpretations to many different people – but a Blak Union Jack speaks to the colonialism and persecution of the Indigenous people in Australia. Kyra’s unique ink print of the Union Jack continues this racial discourse visually. By recreating the Union Jack out of tarleton, a stiff fabric typically used to remove ink from an etching plate plays as metaphor for colonial assimilation. By rubbing the ink back into the fabric, Kyra puts blakness into the flag. The result is a transfer of ink and conceptual ideas, creating an image that stages stark encounters between emblems of colonialism and Indigenous cultural resistance.

For her exhibition, Kyra has created a series of unique ink transfers of the Union Jack in three sizes. Each size is a limited series where each print of the flag varies in composition — making every work unique.

-

Installation view – Kyra Mancktelow: No Blak in the Union Jack, N.Smith Gallery, Sydney.

Installation view – Kyra Mancktelow: No Blak in the Union Jack, N.Smith Gallery, Sydney. -

'There is something sacrilegious about creating a black union jack some 200 years later from the fabric that would have been favoured by some of our most famous colonial characters. Even more so to soak it in the colour that built their empire; blak. '

-

-

No Blak in the Union Jack.

By Coby EdgarIn 1987 Paul Gilroy published a book of race titled; There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation. In the publication Gilroy famously picked apart the left and right of government, making the point that prejudice based on race transcends left-right political divides. Gilroy was appointed as the first black Professor at Goldsmith University of London, and is still very active, holding the position as Director of the centre for the study of race and racism at University College London at the ripe age of 68.

Ten years after Gilroy published this book, in 1997, Kyra Mancktelow was born on Yugambeh Country, Logan, Queensland. Kyra’s father’s is a Quandamooka man and her mother is a Mardigan and South Sea Islander woman; her genetic makeup itself speaks to the colonial history of Queensland. Early colonial Queensland could be described as notoriously racist and economically dependent on slave labour in sugar plantations. Black birded people from the 1860’s onward were stolen from the Pacific Islands, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands, Loyalty Islands, Tuvalu, Kiribati, Fiji and Papua New Guinea. This provided Queensland with much of their wealth and power across the colonies due to their high sugar yield. This continued until The Pacific Island Labourers Act of 1901 was enforced as part of the White Australia policy. What a way to celebrate 6 crown colonies joining as one to form the Commonwealth of Australia. While colonists were kidnapping Indigenous peoples from the Islands, Indigenous Australian’s were massacred, pushed onto missions, their children were stolen persistently and the Union Jack became a symbol of all this to Indigenous people and people of colour Australia over.

It is no surprise then, that the theories of Gilroy have permeated Kyra’s practice. Her work takes the title of Gilroy’s 1987 publication There Ain’t No Blak in the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation taking the ‘c’ from blak to pay homage to the late Destiny Deacon. Deacon took out the ‘c’ that represented the first letter of so many of the racist insults thrown around in the 80’s and 90’s. Black c**t being a favoured by Aussie racists of the time.

Kyra uses the fabric Tarleton in her work; a fabric commonly used by print makers to wipe the ink off the surface of etching plates, as a metaphor for colonial assimilation. Wipe away the black. Kyra rubs the black ink deep into the surface of the starched white fabric, staining the Union Jack black. It is also worth noting that Tarleton was a common fabric used to create the forms and pleats in European garments due to its starched, ridged nature. Tarleton would have been used in pretty petticoats with decorative pleats, to keep the hem of a dress round and splaying outwards, to keep the curve in a bonnet, to stiffen the inner lining of a soldier’s uniform. Kyra rubs black into fabric that was used to create the shapely fashions of the day. The use of the Union Jack makes this work relatable to any person of colour whose ancestors were part of the foundation-making of the colony, the shaping of European progress in Australia. There is something sacrilegious about creating a black union jack some 200 years later from the fabric that would have been favoured by some of our most famous colonial characters. Even more so to soak it in the colour that built their empire; blak.

-

Installation view – Kyra Mancktelow: No Blak in the Union Jack, N.Smith Gallery, Sydney.

Installation view – Kyra Mancktelow: No Blak in the Union Jack, N.Smith Gallery, Sydney. -

-

-

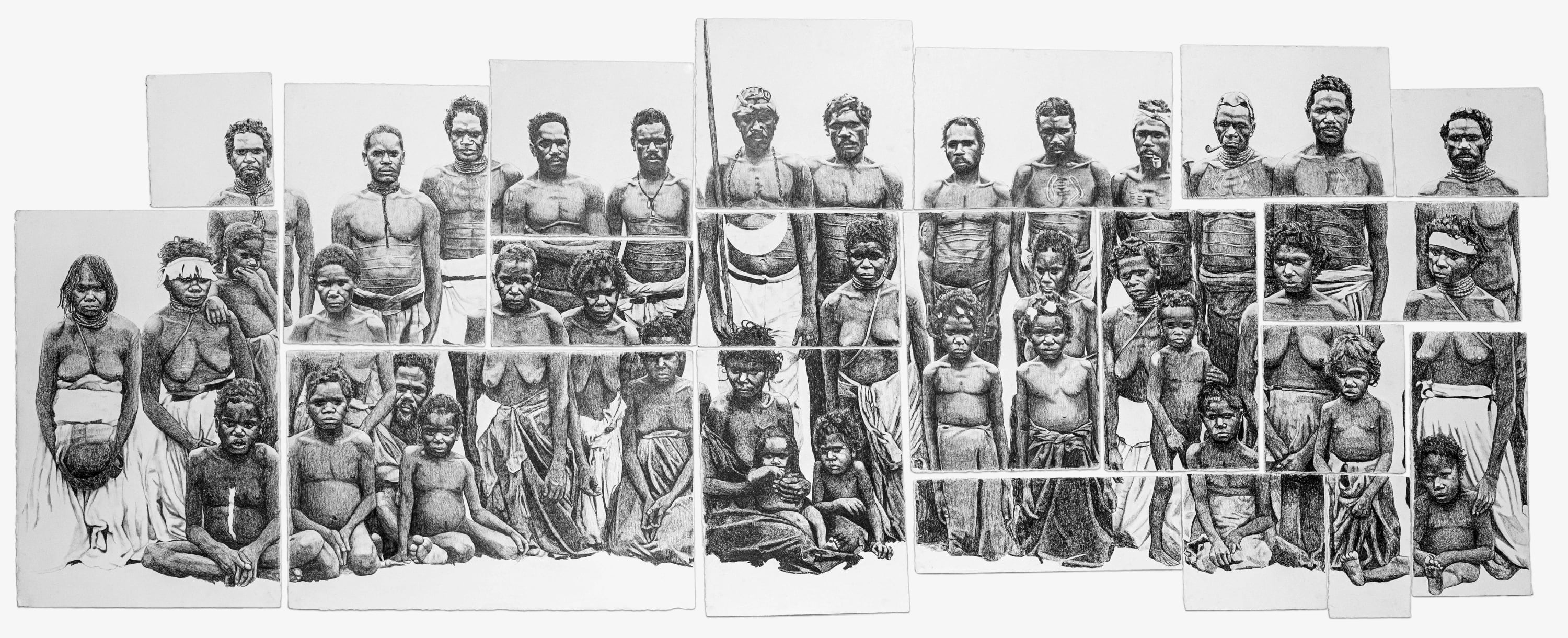

The Story of my People.

Dylan Mooney's multi-disciplinary practice is a personal and moving tribute to the heroism of Australian Indigenous and South Sea Islander peoples whose lives, cultures, and identity were stripped from them or inexorably changed as a result of colonisation.

Presented initially at Cairns Art Gallery as A Story of My People, N.Smith Gallery is proud to exhibit the revised iteration The Story of My People. Delivering a powerful history lesson about what Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander peoples have experienced since colonisation, the exhibition presents three large charcoal portraits of Aboriginal people who were forcibly moved off their country in the Mackay region.

While the portraits reference archival images, they exude a reverence and awe that pays homage to these survivors of a displaced generation. -

Installation view – Dylan Mooney: The Story of My People, N.Smith Gallery, Sydney.

Installation view – Dylan Mooney: The Story of My People, N.Smith Gallery, Sydney. -

'You feel angry, you feel sad but at the same time I feel proud to still be here continuing the work and continuing on the cultural stories that my ancestors have passed down through my family.

-

Dylan Mooneyuntitled, 2021-22charcoal and pencil on paper120 x 450 cmExhibited:Cairns Art Gallery, 2022

Dylan Mooneyuntitled, 2021-22charcoal and pencil on paper120 x 450 cmExhibited:Cairns Art Gallery, 2022 -

-

Dylan MooneyUntitled, 2022charcoal and pencil on paper110 x 270 cmExhibited:Cairns Art Gallery, 2022

Dylan MooneyUntitled, 2022charcoal and pencil on paper110 x 270 cmExhibited:Cairns Art Gallery, 2022 -

The Story of My People.

Coby EdgarState libraries, museums and galleries hold many images and reproductions of First Nations peoples from early conflict days, and when viewed in large quantities or for prolonged periods of time, they conjure a mixture of feelings. Longing, sadness, anger and empathetic distress for those depicted and what they were subjected to, what they endured. Then there is also a spine straightening pride, mixed with effervescence waves of love, from seeing parts of yourself and your family in these images. These slides are usually small. They are aged black and white 19th century photographic glass plate negatives that could easily fit in the palm of a hand. Despite being so small, these photographs are portals into our ancestors’ lives.

The source image depicted is held in the collection of the State Library of Queensland and is of a group of men, women and children. All distant ancestors of Dylan Mooney from the Mackay region. Dylan’s artwork is around 5 metres in length and over a metre in height; he wants people to see the details of the features of his ancestors and experience the intimacy of truly seeing them. There is a sensitivity in Dylan charcoal and pencil drawings that blossoms from a deep love of his ancestors.

When I spoke to Dylan about his drawing practice and this work he spoke from a place of knowing and belonging to these people. Hours and hours sitting with the shapes of his ancestors’ bodies.

The angle of the curls in their hair.

The keloid scars across their chests and arms.

Each individuals’ adornment.

Her reed necklaces.

His metal breast plate.

His moustache elongated by the weight of the hand-carved pipe sitting between his lips.

The depth in her collar bone as her hand reaches down to grasp a child’s shoulder.

Through this practice he remembers them, see them, and comes to know them again.

Gaps between the sheets of paper and people reflect the separation, disposition and dispersal of mob. The constant, unrelentingly cruel colonisation of an entire continent of beautiful, talented, smart, loving people that is still a bottomless well spring of pain for so many. Dylan, through this work, is filling in the gaps for those who have been drowned out in the white noise of history. Reminding us of the stories of those who fought to be heard. Dylan is giving voice to those struggling to speak today of the violence from that place and time. He gently leaves in the gaps between paper the pieces of history that led to this image. Through the faces and bodies of his ancestors he brings us something close to him, he beckons us to see him deeper in time.

For an artist of his age it is a mark of maturity to base his practice on the history of his ancestors in such a nuanced manner. He started with hand drawings using pencil and charcoal as the basis of his technical training and he is a very skilled draftsman. Dylan’s colourful digital illustrations depicting First Nations heroes and queer love give us images of our diverse selves that are not seen by the boarder Australian public. First Nations queer love and herodom is still somewhat scandalous and an absurd prospect; it still makes some people uncomfortable. Dylan does not ask for permission but instead asserts his queer body, thoughts and imagery, simultaneously claiming agency over himself and standing in for queer and First Nations people. He can create versions of us with such joyfulness and self-assertion because parts of him exist in his bodies of work.

It is only through understanding how First Nations lives are a constant balance of pain and love that people can start to know us. I think in knowing Dylan’s reimagining’s of his ancestors you can see how deep the foundations of his wider practice are. He is firmly planted on solid ground. Humble, and gently meeting the world eye to eye, much the same as the ancestors he lovingly recreates for us to bear witness to. If his digital illustrations tell us more about who we are today, his charcoal reimagining of slide negatives show us why his love for his people, First Nations and queer mob, is so unrelentingly loud and proud. He was humbled by the stories of his ancestors before he claimed his own light. His charcoal drawings are his conversations across the expanse of time, a practice of honouring who he is and where he comes from.

-