-

Archibald Prize.

-

-

Not not a mother.

The title of Holly Anderson’s self-portrait, Not not a mother, is a quote from Canadian writer Sheila Heti. Its double negative challenges the social definition of a woman by something she is not. The phrase implies a state of neutrality, a way of being that can be shared by all women.

‘At this time in my life, whether or not I should have a child is a question that I carry around,’ says Anderson, a first-time Archibald finalist. ‘Few decisions seem as binary, or world-shaping, or as routinely brushed off in conversation. I think about it in the studio; is it better to make paintings or make babies? Or find a way, through sacrifice, to have both? The question is existential: how – and for whom – does one choose to live?’

Anderson painted the self-portrait in her studio. Squares of colour arranged on a white primer create a figure in a gridded plane. A bright spot of unpainted space obscures the belly.

‘Is it full of light or empty of colour?’ asks Anderson. ‘My hands hold it lightly – the shape of the future, the weight of my decision.’

-

-

Mum (Hetti).

For this year’s Archibald Prize, Thea Anamara Perkins has chosen to paint her mother, Hetti Perkins, an art curator and writer.

‘I think she’s extraordinary. She’s my mum, so I get to talk her up!’ says Perkins, a four-time Archibald finalist, who is also represented in this year’s Wynne Prize.

‘She’s a champion of the arts and it has been a privilege to be surrounded by the many artists and arts workers who are drawn to her and her nurturing ways, many of whom we now consider family.

‘In her work as a curator, she has set a precedent of hard work, consultation and the practice of putting artists first. I want to celebrate curators and people working in the arts, because their contributions are the reason we understand, platform and value First Nations art,’ says Perkins.

‘Mum is a very strong woman and has captained our family’s little ship through troubled waters. She is now living in Mparntwe/Alice Springs, and I wanted to include Country as another figure in her portrait.’

-

-

The Marriage of Nicol and Ford.

Fashion designers Katie-Louise and Lilian Nicol-Ford are the masterminds behind the high-concept, inclusive and imaginative demi-couture label Nicol & Ford. They are also married.

Asked by Natasha Walsh which historical artwork they would like to reimagine, they chose the celebrated French painting Gabrielle d’Estrées and one of her sisters c1594 by an unknown artist, now in the Louvre, Paris.

It portrays Gabrielle d’Estrées, the mistress of Henry IV of France, sitting naked in a bath with her sister, who is pinching her nipple. In a room behind a curtain, a woman sews baby clothes. The painting is thought to allude to d’Estrées’ royal pregnancy.

‘We were drawn to the debate surrounding the work’s Sapphic undertones and the intended audience for this eroticised performance,’ says Walsh, a seven-time Archibald finalist.

‘Katie and Lil wanted to reimagine it through an explicitly queer lens. In our version, it becomes a celebration of their relationship and combined creativity through the birth of Nicol & Ford. The room behind the curtain is now a version of their studio where a duplicate Katie sits sewing, their dog Maestro at her feet. Katie and Lil are nude without being naked; revealing while retaining their private selves.’

-

Wynne Prize.

-

-

Grey nomadic visions.

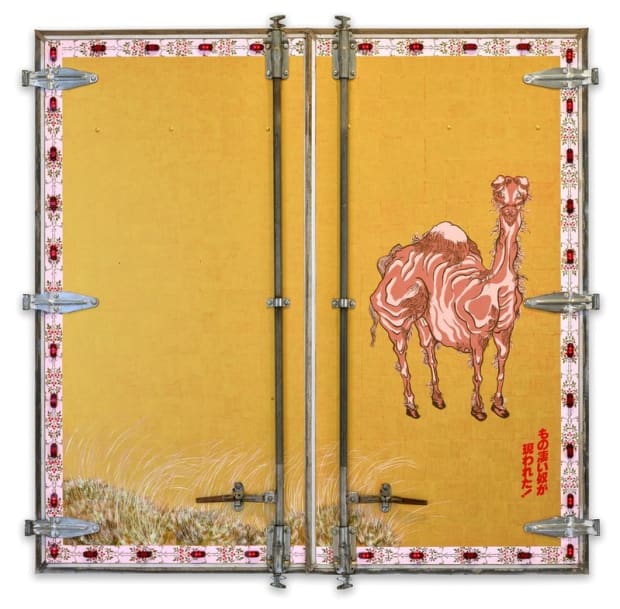

Grey nomadic visions directs us to an everyday view from a driver’s seat: the rear doors of trucks that move commodities across Australia. Winners of the 2022 Sulman Prize, Claire Healy and Sean Cordeiro enliven the truck doors with gold paint, LED lights, a ‘Blackberry’ pattern attributed to 19th-century English designer William Morris, and a camel.

Synonymous with nomadic cultures in the northern hemisphere, the camel – like the blackberry – is an invasive species in Australia, introduced for the transport of goods between desert outposts. Beyond these references, the artists also nod to Dekotora (Japanese decorated trucks); Yokohama-e woodblock prints, depicting Western traders in 19th-century Yokohama; and Razorback, the 1980s Australian desert-horror film.

Inspired by a previous collaboration with Martu artists from the Pilbara region of Western Australia involving weaving and reclaimed car parts, Healy’s and Cordeiro’s darkly humorous work upends romantic notions of Australia’s sunburnt landscapes. Bringing the tangled connections between colonisation, consumption, leisure and environmental damage into our field of vision, its flashing red lights offer both decorative relief and instructive warning.

-

-

Atherreyurre.

This is Atherreyurre in Mparntwe, also known as the Telegraph Station in Alice Springs, Northern Territory. It is a site of significance for Thea Anamara Perkins, a two-time Wynne finalist who is also exhibiting in this year’s Archibald Prize. This is where her grandfather Charles Perkins was born and where he rests, and where her great-grandmother Hetty Perkins worked.

The seductive beauty of Perkins’s work, with its atmospheric evocations of burnished light, draws viewers into a tender trap set to expose the looming threats of climate inaction. ‘Beauty can be a vehicle to convey hard truths,’ she says. ‘I chose to paint last light as time is running out. I’m communicating the essence of a place that I hold dear to prompt others to think of what we value.’ Thus, this painting, which echoes the energetic rhythms of landscape, becomes a portrait of the people connected to it. As Perkins explains, ‘Country is family.’

-

-

Who said possession was 9/10ths of the law.

There is a greed about colonising someone else’s land, an agreed greed that continues today and a lack of sensitivity to the original inhabitants of this land and the land itself.

There is a disconnection with nature and a self centeredness that defies care .

Whenever I am in the bush I see signs of humans making their mark on nature.

I see graffiti tags on rocks, I see love and hate, political messages, personal tags, words like fuck, initials and love hearts

This colonial woman, who could be any of us, sprays the word mine, which is about personal ownership but also about mining the land

There are also the tags of Macquarie and Banks and other colonial figures that talks of their takeover & tagging is a way of marking territory or like a cat spraying or marking its territory.

Using hi vis yellow a colour that can’t be missed, a colour that holds power, she is taking possession and we are complicit. -

-

Tapestry: Lotus.

A first-time Wynne Prize finalist, Louise Zhang was inspired to record her experiences of sitting by the lotus pond in Sydney’s Royal Botanic Garden, located on Gadigal land. The work stems from a practice of ‘slowing down and simply being,’ Zhang explains, with the act of painting offering an opportunity for reflection and providing solace. Found at the harbour end of the gardens, the pond is a site that Zhang has enjoyed since childhood.

In this painting, Zhang imbues the ancient Chinese symbol of the lotus with a pop sensibility. Flourishes of purple–pink coalesce around a focal point that frames a blossoming lotus – a flower traditionally associated with elegance, longevity and other virtues.

‘I’ve reflected deeply on the concept of an “Australian landscape”,’ Zhang says. ‘My artwork has been interpreted in this context before but was never fully recognised as “Australian”, like me. I see my experiences with our landscape as inherently “Australian” and intertwined with my Chinese–Australian heritage.’